Boeing has had a turbulent second and third quarter this year. It was related to the worldwide grounding of the Boeing 737 Max following two fatal 737 Max crashes that were blamed on new anti-stall technology installed on the new Boeing 737 Max. Boeing shares soared above $380 in the last week of September, hovering at the highest levels since the 737 Max was grounded in March 2019. This is nearly a 29% rebound from its mid-August 2019 low of $320. The rally began shortly after Reuters reported in late August that Boeing announced that it anticipates to ramp production to 52 737 Max aircraft by February 2020 and 57 737 Max aircraft by July 2020 if regulators approve the 737 Max for flight in the fourth quarter of 2019. As it stands Boeing has already scheduled its first round of pilot trainings in Miami for this week and is scheduling additional trainings in the UK, Singapore, China and Turkey. The stock is still 20% off of its record high of $446 in late February-early March of 2019 just before the 737 Max was grounded. Many investors would argue that Boeing has already reached correction territory and share prices will at worse remain in the mid-$300 with the worst now behind them. Some experts would argue otherwise and say that it is unlikely Boeing will meet this highly optimistic goal anytime in the foreseeable future. Unfortunately, Boeing stock prices are just about the only aspect of Boeing that is seeing clear blue skies for the time being. As for the rest of Boeing, expect to see continued turbulence.

Boeing has issues with suppliers, grounded aircraft with no end in sight to resume flight, mounting pressure from regulators, airlines and workforce.

Even if Boeing manages to come up with a solution to fix the inherent problem plaguing the 737 Max and the plane resumes commercial flight, there is no guarantee that they will be able to meet their goal of producing 57 planes per month by June 2020. This is because the 737 Max problem is the result of ongoing systemic issues at Boeing as a whole, and there are many. Here are just a few problems.

Leadership Asleep in the Cockpit

The 737 is Boeing’s most popular narrow-body short-to-mid range commercial passenger aircraft and is Boeing’s bread and butter passenger aircraft. The original 737 was first introduced in the early 1960s and has gone through several major updates since then. In 2006, Boeing first announced major updates to the 737ng (next generation) which had already been around since 1993. Yet development was not green-lighted until 2011, only after Airbus unveiled the new more fuel-efficient Airbus A320neo (new engine option).

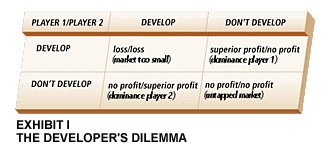

It’s not that Boeing lacks innovation, but rather, they suffer from developer’s dilemma, a problem commonly encountered by most companies in highly competitive markets. Martin Kretschmer explains this dilemma in his article, Game Theory: The Developer’s Dilemma. Viewing the development of new aircraft from the perspective of Boeing executives, one can argue that tapping into new markets or even changing historically successful markets is risky. However, the risk of not tapping into a new market is just as risky, especially if there is fierce competition from a rival company.

The developer’s dilemma when two rival companies are involved offers four different outcomes in the form of a quadrant. If Company A develops a new product and Company B does not, Company A gains 100% of the new market share (potential monopoly) and Company B loses any opportunity to capture any portion of market share in that new market. If the new market is overestimated, Company A loses money as a result of tapping an unknown market and this puts Company B at an advantage. If both companies decide to develop in a new market, they both risk losing big and if there are profits to be made, the potential earnings must be shared. The cautious approach to allow your direct competitor to enter unknown territories first as the beta tester is arguably a good move when the financial risks are high. However, in this instance, Boeing did not consider which territories their competitor was “beta testing” and the success they would have in the market. For example, a feature with undermined importance to Boeing was fuel efficiency. Fuel costs account for as much as 25% of the total operating costs for airlines. A new, more fuel efficient 737 should have been considered a necessity rather than a risky development. However, Boeing failed to act on this in the development phase. With Airbus going all-in on innovation with a new A320 featuring a fuel-efficient engine option, Boeing should have anticipated high demand and incentive for such options considering fuel expenses for airlines and prioritized them as airline fleet replacements to the very popular, yet aging and less fuel-efficient, narrow-body aircraft.

Do a Quick Fix When the Clock Ticks

With the incoming competition, Boeing executives were pressured to produce a new 737 in a short period of time. Typically, such an undertaking can take many years, but Boeing already had another plane, the 787 Dreamliner also in development and several years from being production-ready, the cards were stacked against Boeing. The reality is, Boeing could not afford to spend upwards of 10 years to develop another new aircraft that would secure Boeing’s market share position. The short-medium haul narrow-body segment is highly competitive. American Airlines, who historically ordered narrow-body planes from Boeing, had already ordered 130 of the new fuel-efficient Airbus A320neo jetliners. So, in an attempt to cut the time from development to production, Boeing decided to retrofit their existing 737ng with a new, more powerful and fuel-efficient engine power-plant, along with new technology and updated interior options that an airline can easily reconfigure and modify.

The problem with the new engines is that they were originally designed to power the much larger 787 Dreamliner. The engines were too powerful and positioned too high and close to the front nose for the new 737s. Engineers feared that this would cause the plane’s nose to abruptly pitch up during flight, which could potentially cause a stall.

Instead of developing a more suitable engine and engine placement for the 737, they opted to develop an anti-stall system which relies on a AOA (Angle of Attack) sensor that communicates with an MCAS (Maneuverable Characteristics Augmentation System). This solved the potential stall problem, however, issues with metal shavings left inside the frame may have caused the sensor to short circuit and fail, sending incorrect pitch readings to the MCAS and forcing the plane into a nosedive. The original design had only one sensor. They added a second sensor since then. The currently proposed fix would require both sensors to have similar readings before sending any signal to the MCAS system. In addition, the modification would only allow the MCAS system to pitch the nose down once, and with a more limited pitch that pilots can safely correct.

According to one Forbes report on the 737 Max, experts argue that adding a third sensor could serve as a tie-breaker should one of the sensors fail to provide a proper reading. Former Boeing engineer Peter Lemme told the Washington Post regarding the two AOA sensor problem, “If one’s wrong, you can’t take the average of two, and you can’t use the good one, because the computer doesn’t know which one is right.”

Outsourcing Solves Everything

Boeing has historically produced and assembled its planes in the Seattle area. Why change what works? Time and money is usually the catalyst. During its development, the 787 Dreamliner not only boasted the latest technology, but it was also the first commercial airplane to use carbon fiber, a material much stronger and lighter than aluminium, for better fuel economy. The 787 Dreamliner was Boeing’s greatest and boldest achievement in modern aviation. However, in an attempt to contain manufacturing and labor costs and improve production time, the executives at Boeing decided to outsource much of the 787 Dreamliner’s parts, including the plane’s entire structure, to manufacturers in other countries. Purchasing prefabricated materials, theoretically, would reduce in-house inventory, assembly time, and financial risk by spreading it across many suppliers.

However, this did not happen. Unfortunately, excessive reliance on outsourced suppliers created more delays than anticipated. To make matters worse, there was a lack of expert knowledge to correct unforeseen problems. These problems included parts that didn’t fit with others because most parts came from manufacturers who were all from different countries than one another. Many times, parts arrived either partially assembled or incomplete. Other times, parts would arrive out of sequence along the assembly process. For example, fasteners varied between manufacturers. The temporary solution was to color-code temporary fasters so that they may be replaced when the correct fasteners arrived. The assembly process could not progress until after all fasteners were replaced with permanent fasteners. Temporary fasteners were tracked by color-coding them. The lack of coordination and troubleshooting along the supply chain, in general, created difficulties for Boeing which had delivery commitments major airlines. The worst example of bad outsourcing involved the aircraft’s (fire-prone) battery which was manufactured by a company in Japan and assembled by another company in France, which contributed to the grounding of the 787 Dreamliner.

The outsourcing strategy on behalf of Boeing caused more delays and cost Boeing more in the long run. Boeing spent billions of dollars to re-engineer entire sections of the 787 Dreamliner in-house and to improve processes along the supply chain. Though issues known regarding the 787 Dreamliner were resolved, it delayed delivery of the first aircraft to ANA by 3.5 years. Approximately 70% of 787 parts are outsourced from some 50 suppliers from 135 different locations and delivered to Boeing’s assembly Seattle and Charleston assembly plants. It is also possible that we may see a significant negative impact on Boeing and their outsourcing operations as mounting uncertainty over supply chain costs arising from ongoing trade tensions between the US and other countries create market instability.

If You Don’t Know of Any Problems, There Aren’t Any

Boeing is no stranger to sending planes out that are far from flight-ready. Though the Dreamliner and the 737 Max have a well-documented history of problems ailing the company, this is nothing new. In 1965, the recently unveiled 727, which was touted as one of the most advanced aircraft of its time by Boeing, had suffered three crashes within three months, killing all people on board all three aircraft. The problem turned out to be with the wings. The unusually larger wings allowed for a greater lift at lower speeds. This was supposed to be more helpful for airports in urban dense areas with higher air traffic. Though there was nothing wrong with the aircraft itself, Boeing failed to provide adequate pilot training on the plane’s unique flying characteristics, which in turn, included a much faster sink-rate that proved catastrophic for unfamiliar pilots.

In the 1990s, the 737 suffered three incidents, two of which resulted in fatalities, before NTSB finally discovered the root of the cause- faulty rudder servers that caused equipment to jam on runway approaches. Another premature launch on behalf of Boeing was the 787 Dreamliner, which as mentioned, suffered major setbacks related to outsourcing. Though not the sole problem that resulted in the grounding of the 787 in 2013, major electrical problems that plagued the Dreamliner can be largely attributed to the fire-prone battery system that was linked to two separate incidents that same year. While Boeing has always outsourced its battery from suppliers, the fact that most of the parts were outsourced for the 787 Dreamliner could be the reason why oversight by Boeing engineers could be blamed on the flood of supply issues stemming from an over-reliance on outsourced parts for the 787 Dreamliner.

In February of 2014, wing manufacturer Mitsubishi Heavy Industries had notified Boeing of possible stress cracks on 787–9 Dreamliners (a new version of the 787 in production), due for delivery later in the year. Boeing was quick to notify customers and informed that none of the current 787 Dreamliner aircraft already in service was in any danger of being affected by the problem. In 2019, a different story- when the 737 Max using new technology that was not fully vetted and not yet well-known to pilots who were trained to fly the previous 737 planes had AOA sensor failures, which sent incorrect signals to the MCAS to dip the plane into a controlled nose dive to prevent a stall that never happened. This problem is to blame for at least two major aircraft disasters mentioned later.

It Just Needs To Fly, Theoretically Speaking

Boeing has been accused of cutting corners by outsiders and more notably by its employees, some of whom reportedly blew the whistle on Boeing to FAA officials shortly after the findings were released regarding the crash of Ethiopian Airlines flight 302. Joseph Clayton, a technician at Boeing’s North Charleston plant, along with over a dozen current and ex-employees went into great detail on the shenanigans at the plant in a New York Times article that was published just one month before the grounding of the 737 Max. The New York Times article (which mentions one pervasive problem involving metal shavings that were frequently left behind inside the plane, dangerously close to electrical components) interviewed Joseph Barrett.

Mr. Barrett claimed that he repeatedly urged his bosses to ensure that production removed the shavings. The FAA confirmed the claims and danger the shavings pose, including short circuiting and potential fires, resulting in the mis-signaling of the plane’s software that has been cited as the cause in multiple disasters. The FAA discovered metal shavings on aircraft certified by Boeing as debris free as recently as 2017 according to Kris Van Cleave from CBSNews.com. Cleave also reported that out of the four whistleblower employees and ex-employees who contacted the FAA on April 5, 2019, one attributed foreign object debris (FOD) in the form of metal shavings as the potential cause of the failing AOA sensors that caused the crash of Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 and Lion Air Flight JT610. This problem is actually so well known that the Air Force refused delivery of the 767-based KC46 refueling aircraft on two occasions because they discovered FOD.

In a May 9, 2019 article published by Bloomberg Businessweek, Peter Robison reported that Boeing invited FAA engineers to Boeing to inspect new mock-up simulators of the new 737 Max to determine if existing 737ng pilots would be required to receive Level D training, a level that would require at least 20 hours of pilot flight time training on actual 737 Max aircraft to be certified to fly the new 737 Max aircraft or if they can be certified to fly the new 737 Max with Level B training, a training that only required a 2 hour training that could be completed on an iPad. This would allow Boeing to speed up delivery of planes for immediate circulation into commercial use.

Former Boeing engineer Rick Ludtke has been critical of Boeing’s management. Ludtke told Businessweek “[Boeing] were targeting the highly paid, highly experienced engineers,” which he believes diminishes the quality and safety over time. “They do it strictly by cost, and they do it more so with every airplane.”

Delays and Cancellations, Not the Kind Passengers Experience

Boeing has an extensive history in delivering new orders on time. Problems with the production line, testing issues and delayed FAA certification have all led to delays of new aircraft. Supplier problems, quality control issues and work stoppages have all created production bottlenecks in the past. ANA, the first airline to place an order for 50 787 Dreamliners in 2004, had an expected first delivery for 2008 but did not receive its first aircraft until 2014, a six-year delay. ANA budgeted the fuel cost savings into their expense forecast for 2008 going forward. Unfortunately, these projected savings weren’t captured for a full six years because of the delay.

When the 737 Max debuted, it quickly became the darling of Boeing and the favorite among airlines. Boeing sold more than 5,000 airplanes since its debut making it Boeing’s fastest-selling airplane in Boeing’s history. Boeing sold 0 planes since its grounding in March of 2019. Canceled orders, delayed deliveries of existing orders and unclear timeline as to when the 737 Max airplanes will be certified to resume flight and production all leave a cloud of uncertainty for airliners.

This creates a higher demand for Boeings fiercest competitor, Airbus. Many airlines who have remained loyal to Boeing until now may find it more difficult to stick around. This is good news for Airbus, bad news for Boeing.

In July, State-run Saudi Arabian Airlines-owned based budget airline Flyadeal cancelled their order of 30 737 Max that included an option for an additional 20 737 Max aircraft, a value of $5.9B if the aircrafts sold at list price. To add insult to injury, Flyadeal announced a new deal for 50 A320neo planes from Airbus. The opportunity cost to airlines and Boeing as a result of delayed deliveries, cancelled orders and new orders with their direct competitor underscores how the problems at Boeing directly affect Boeing’s future earnings, the airline’s future earnings and ultimately, the fuel costs that could have been avoided that are eventually passed on to the passengers through airfare prices.

Mounting operating losses faced by Boeing due to cancelled and delayed orders aren’t the only thing Boeing has to worry about. Boeing has to face the music and make things right with the airlines who purchased and took delivery of the 737 Max which are now in their seventh month of grounding. The grounding amounts to huge losses for the airlines that relied heavily on their 737 Max fleets and had to cancel thousands of flights as a result of the grounding. Southwest and other airlines are also mitigating their losses by negotiating settlement agreements with Boeing for losses caused by the 737 MAX grounding according to a CNBC report. So far in the second quarter of this year, Boeing has set aside $5.6 billion to cover airline losses for flight cancellations resulting from the 737 MAX grounding. Southwest, an airline that has almost exclusively used the 737 since 1971 has reported at least a $225 million thus far according to a report from The Dallas Morning News in August of 2019.

How Many Lawyers Can You Fit Inside a Grounded 737 Max?

Russian airplane leasing company, Avia, recently filed a lawsuit seeking not only a return of its 35BN deposit but an additional $100 million in damages. This is one of many airline companies we should expect will sue Boeing for damages resulting from the grounding of 737 Max airplanes. Over 3,000 pilots from 12 different airlines have also filed a class-action suit against Boeing for lost wages resulting from the grounding of 737 Max airplanes. Boeing announced back in July that it would set up a financial assistance fund to be paid to the families of the people killed in the two 737 Max crashes. On September 23, Washington lawyers, Ken Feinberg Camille S. Biros, the administrators of the fund, announced that the fund “will begin accepting claims from family members immediately,” according to Reuters. Each family will receive $144,500 for each person killed, a total of 346 fatalities. The claims must be received no later than December 31, 2019. Any claim paid out to the families will not require family members to waive their right to file wrongful death lawsuits in the future, which could amount to billions of dollars in legal liabilities. Acknowledgement by Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg that the new anti-stall system on the 737 MAX contributed to the two fatal crashes along with mounting evidence against Boeing’s assembly process that may have led to the system failure has exposed the aircraft manufacturer to mounting legal woes.

Workforce Morale Is Also Grounded

Labor disputes are nothing new to Boeing. Boeing has a history of union-led strikes and a tumultuous relationship with the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers (IAM). They have a history of union-led work stoppages at their Seattle, WA plant. Wage and benefit disputes have led to union-led strikes. More recently, Boeing’s controversial decision to open a plant in South Carolina has led to accusations that Boeing opened the new plant in an attempt to crush the union.

The National Labor-Relations Board (NLRB) stepped in to file a Federal complaint against Boeing for opening up a non-union plant in South Carolina. The complaint was withdrawn after Boeing came to an agreement with the IAM. Finally, after a failed attempt to form a union at the North Charleston plant in South Carolina in 2017, the votes finally passed and the union was formed in 2018. This was achieved in spite of Boeing’s aggressive radio-ad campaign and attempts to delay and even stop the election from occurring. They are appealing the election results to National Labor Relations Board.

Trust Issues

The 2019 Paris Air Show gave Boeing an opportunity to take new orders of the 737 Max. Even with the likelihood of deep discounts, only International Airlines Group, the parent company of British Airways and other smaller airlines placed an order for 200 737 Max airplanes at an undisclosed price for a 2023 delivery. It marked the first sale of the aircraft since its grounding in March of 2019.

It will take years for Boeing to regain the trust of even its most loyal customers who are now looking towards future orders with Airbus. In an ironic twist, the 737 Max, which was quickly becoming the most popular aircraft in modern passenger airline history, has instead turned into the most infamous plane in Boeing’s history. We are only at the very beginning of what is sure to become one of the most examined case studies in both the engineering and business communities.

Turning Things Around

There are many problems plaguing Boeing. Fixing a few issues with planes and suppliers won’t be enough to secure their current market share. The executives at Boeing have an opportunity to change the company around and must do so if they appreciate their customers and investors. But is Boeing doing enough?

***Update: Just hours before this article was submitted to Data-Driven Investor for publication Boeing announced that it will create a new Safety Committee. Though it appears to include some of the recommendations in this article according to CNBC, I have not had an opportunity to do a sufficient ‘deep dive’ to comment. What we do know is that the committee:

“will oversee the safe design, production and delivery of the company’s aerospace products and services, Boeing said on Wednesday.

Boeing said Adm. Edmund Giambastiani Jr. , former vice-chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, will lead the committee, which was created at the board’s meeting in August.

Other members include Duke Energy Corp. Chief Executive Lynn Good and Lawrence Kellner, who once led one of the predecessor companies of United Airlines Holdings Inc.

The board, led by Chairman and Chief Executive Dennis Muilenburg, also amended the company’s governance rules to make safety-related experience a criteria it will use in choosing future directors, the company said.”

— The Wall Street Journal, September 25, 2019.

It starts with the corporate culture in every aspect of the company’s operations:

Better communication will improve quality and workflow: Work more closely and in partnership with regulators, pilots, airlines, customers, and outside experts to find solutions to existing problems such as those found in the 737 Max and actively engage and involve all of the stakeholders when developing a solution to the problem.

Focus more on the system behind the problems to ensure problems won’t persist. Learn from the experience and make the necessary system adjustments to prevent future manufacturing and assembly problems. Take a more proactive approach when solving the problem. Examine what occurred in the system that led to Boeing’s current and past woes.

Take a proactive approach when potential problems are discovered and develop a system that encourages employees to report problems in the interest of safety, quality and system improvement. Create a whistleblower policy to report unsafe conditions and concerns about quality without fear of retaliation from their supervisors. Train employees to make it their duty to immediately report problems and hold people accountable when problems are not immediately reported. Ensure that this process is independent, where engineers have the authority to make decisions, recommendations and enforce the necessary adjustments, free from financial influence.

Embrace transparency and inclusion. Develop a procedure plan that notifies, updates and welcomes input from all stakeholders including employees, airlines, airline pilots, independent consultants and suppliers when potential problems arise and corrective actions are put in place. Promptly notify airlines and regulators of potential issues before they occur and develop corrective action plans that are independent of financial decision-makers. Ensure that airline pilots and airline maintenance crews are provided with the necessary tools and support to implement corrective action plans in a timely manner that is independent of financial scrutiny.

Focus on safety over profits and the profits will eventually follow. Surely, the cost involved to ensure the highest level of safety and quality is minuscule in comparison to the financial costs already incurred by Boeing otherwise. Scrap safety procedures that do not work. Start from the ground up with new systems that better address issues that have plagued the company in the past.

Frequently evaluate, scrutinize and improve the current minimum standards and ensure that with each evaluation, there is an improvement to the current minimum standards in each process involved in manufacturing and assembly. Create policies that allow employees to evaluate current minimum standards in their areas of expertise.

Educate and train employees continually on safety and quality, particularly as it pertains to minimum standards and hold employees, managers, contracted independent inspectors and suppliers accountable when minimum standards are not met.

Push for improvements industry wide. Innovate safety and share innovation with the airline industry as a whole, including direct competitors. Focus on educating the industry, from airline executives and airline crewmembers to all stakeholders, about all of the initiatives to change the corporate culture, thus sending a clear message that it is no longer ‘business as usual’ at Boeing. Go public whenever possible, when concerns arise, even if the stock price takes a hit. The hit is always short term. In the end, analysts will make their own determination on the direction the company is taking, and the stock value will continue to rise in the long-term.

Remain proactive with reparations. Provide ongoing assistance and support the families of victims from fatal crashes. Negotiate cost reparations to airlines to ensure the long term relationship between Boeing and the airlines remains as a solid partnership. Make it Boeing’s business to look out for all affected stakeholders.

Take accountability and full ownership for failures as well as successes. Demonstrate how you are leveraging the experience gained from past failures in all of your processes. Trust will be regained once the industry and regulators see full attrition and commitment towards improving quality and safety in every aspect of Boeing’s operations.

Boeing has a lot of issues that will not be corrected overnight. For years Boeing has been a valuable and profitable company that has employed generations of families with commitment and pride. The company has always seen turbulent times and has remained viable and profitable, but the margins for tolerance during turbulent times have eroded. In much the same way there is no margin of error afforded to pilots that are expected to take us to our destinations, Boeing cannot afford to make any mistakes. It all starts at the C-level.

Disclosure: The information in this article is for informational and discussion purposes only and does not reflect the opinions or sentiments of Data-Driven Investor. This and any other articles posted on Medium, Data-Driven Investor, or other blog sites may have specific dated information that may no longer be relevant and/or reflect the views or opinions of the writer at a future date.

In the interest of full disclosure, though I may not own any direct shares of Boeing (BA) stock at the time this article, I may own shares by way of investment funds. I am not affiliated with any financial institutions. I am not an institutional investor, certified financial advisor or a professional investor. Neither Data-Driven Investor or I endorse or recommend any investment decisions. Neither Data-Driven Investor or I offer any financial advice in this article and any information provided in this article should be not be construed as such. Be advised that investing in any security that is not FDIC insured can result in losses that include loss of initial capital. Speak to a certified financial advisor to discuss the risks and your best options before you invest.

Excellent article I just read on Boeing. Full of facts and history on how airlines compromise on safety to outdo competition for market control.

There is new information as to who exactly knew about failures in Boeing’s 737 Max Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) during simulation tests from text messages dating back to 2016, according to The New York Times, Washington Post, Reuters and other major news outlets today. Though it is widely believed a failed angel of attack (AOA) sensor, which sends information to the MCAS is to blame for the two recent fatal crashes, this new evidence could suggest the MCAS itself is to blame. That would put any current fix plans and return to flight in the near future for the 737 Max back into question. This is potentially devastating news to airlines who have grounded entire 737 Max fleets as they prepare their fleet schedule for busy upcoming holiday travel season. #boeing #boeing737 #boeing737max https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/18/business/boeing-flight-simulator-text-message.html?smid=tw-nytimes&smtyp=cur