Why is Pluto no longer a planet? The question perplexes physicist, former ABC News science editor, author and teacher Dr. Michael Guillen. He contends this science silliness must change.

The is-or-is-not-a-planet dust up also bugs University of Central Florida planetary scientist Dr. Philip Metzger. He took up Guillen’s cause and threaded his way through three centuries of planetary back and forth on Twitter, showing what happens when scientists get the right to vote:

Michael Guillen weighs in on planets. He is right, saying concepts like “planet” shouldn’t be voted on. The point of science is to evolve our conceptualization of things. There is a deep, interesting history of how “planet” evolved in the tug of war between science and culture.

There were four main events in the evolution of “planet.” The first was the Copernican Revolution, where scientists rejected the dynamical concept — wandering stars orbiting Earth — and replaced it with a geophysical concept: Planets are bodies like Earth, regardless of what they orbit.

That concept was embraced by astronomers for over 300 years until sometime in the 1900s. Around 1920, evidence shows that scientists simply forgot that moons are also a type of planet. That’s when the textbook definition of “planet” stopped including moons as planets.

I say they “simply forgot” because we can see there was nothing happening in planetary science that drove a change in the definition. Instead, we see use of terminology slowly drifted as a pure Gaussian — non-driven diffusive process — until moons were rarely called planets.

That’s when textbooks stopped giving the historic definition that existed for over 300 years since Galileo. The idea that planets have to directly orbit a star was introduced by default, no scientific reason. Dynamics had made a sneaky comeback into the concept of a planet.

That laid some of the groundwork for the bad vote that happened in 2006.

Culture bias affects everyone

When we ask, why did astronomers default to putting “orbits” back into the concept of a planet, there’s no known answer except it must’ve been cultural bias. Scientists are affected by culture, too.

And why does culture default to making moons not planets, holding a concept that planets must orbit a star directly? I can’t see any answer in the record other than it is similar to the older geocentric view, where planets are orderly in a tidy sequence.

On the other hand, in the 1960s, planetary scientists started calling moons “planets” again. By then, spacecraft missions were visiting those planets, and we rediscovered that the historic concept we had from Galileo — purely geophysical with no reference to what a body orbits — is still useful.

But sadly, the community was fractured by then, and at most, astronomers weren’t dealing with the geology in comparative planetary. So, they never went back to the historically useful concept of “planet.” Most astronomers kept orbital dynamics as part of their concept.

Historically, planets that orbit a star directly are called “primary planet” — or just “planet” for short — while “secondary planets” are also called “satellite” or “moon.” “Secondary planet” is too verbose, so it fell out of favor. Thus, astronomers forgot that moons are planets.

After the Copernican Revolution, that was the second change that happened in the concept of a planet. A generation of astronomers were not explicitly taught that dynamics is irrelevant to planethood. That was all it took to get screwed up.

It was 1920 to 1960 when that occurred.

Planetary trailblazer

To recap: Galileo found lunar mountains, so he forged a new concept of “planets.” They are geophysical objects like Earth — including moons. This new concept was born from alignment with new theory, and so it replaced the old dynamical concept. He had to fight culture over this.

Then, over a period of 300 years, astronomers kept including moons as actual planets, because there was no change in the theory and thus no motive to forge a new concept of “planet.” Every textbook for 300 years explicitly said that moons are planets.

But, slowly astronomers changed terminology and forgot the term “secondary planet.” There was no science driving that change. Nobody was arguing that moons are different than planets. On the contrary, the commonality of moons and primary planets was often used in scientific papers.

So the second major change in the “planet” concept appears to have been primarily a cultural influence rather than scientific. It will take more space to fully make this argument, and a paper is forthcoming.

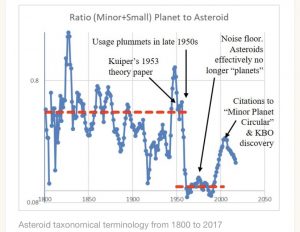

The third major change in the concept of “planet” involves the size of planets. There was a long trend through the 1800s of finding ever-smaller asteroids, and they were all included as primary planets. They were abruptly made non-planets following a paper by Gerard Kuiper in 1953.

Pierre-Simon Laplace’s old planet formation theory was believed to be proven by the asteroids. So, a concept of “planet” that included asteroids was aligned with that theory. Kuiper’s 1953 paper on accretion theory split the “planet” concept into two groups, so asteroids became non-planets.

The bibliometrics shows that astronomers quickly stopped calling asteroids “planets” in the late 1950s. Papers on theory called them planets right up to Kuiper’s 1953 paper then immediately stopped calling them planets.

So, what was the essence of this third concept change?

Life enters the fray

Galileo gave us the concept that a planet is a geophysically complex body like Earth. All astronomers began arguing the complexity of all the planets, even the idea they all possess life. By including the ever-smaller asteroids, we were undermining that concept, in effect.

By removing asteroids from the concept of “planet,” scientists were restoring Galileo’s concept that they’re Earth-like complex geophysical bodies. This was motivated by science, aligning the planet concept with theory. This was good. That’s how science is supposed to work.

Strangely, in this third case, scientists didn’t have to fight culture, and they weren’t submitting to culture either. Culture had never accepted the asteroids as planets. Science happily moved to a concept that culture already held. Nobody got tried — like Galileo did.

The essence of this third concept change was that a planet is geophysically complex, but small asteroids are not. Papers argued that asteroid Ceres is a planet for precisely this reason.

This concept aligned usefully to support new theory, which is how science works.

Orbit-clearing invention

So now, the fourth major event in the concept of a planet: the vote in 2006. They said a planet is “an object that clears an orbit.” That is a completely different concept than we ever had before. It was designed to select roughly the same set of eight or nine objects, but to do so they invented an orbit-clearing idea, never part of the concept ever before.

It was motivated in the interplay of science and culture, again, but this time the astronomers unwittingly rejected science for culture. Look at the arguments on both sides.

As far as I can tell, the underlying motive was to preserve the idea that planets are “special,” reflecting an orderliness of nature that culture desires. It was easy to fall into that: The idea that moons aren’t planets already injected dynamics into the concept held by most astronomers.

It wasn’t motivated by newly developed theory like the case with asteroids. But presentism — wrongly interpreting past events by projecting current beliefs onto people who lived in the past — was used to misinterpret the history of how asteroids became non-planets.

Presentism is also what keeps astronomers nowadays from grasping that moons have always been true planets, since the Copernican Revolution and even before, and that until very recently “orbiting a star” was never part of the concept of a planet — except in culture.

This interplay of culture and science is fascinating. We see four different ways that it played out in the four different events affecting the concept of “planet.” It makes you wonder, why are planets so darned important to culture? Culture doesn’t care about the definition of beetles.

Why are planets so darned important to culture?

4 min read

Why is Pluto no longer a planet? The question perplexes physicist, former ABC News science editor, author and teacher Dr. Michael Guillen. He contends this science silliness must change.

The is-or-is-not-a-planet dust up also bugs University of Central Florida planetary scientist Dr. Philip Metzger. He took up Guillen’s cause and threaded his way through three centuries of planetary back and forth on Twitter, showing what happens when scientists get the right to vote:

Michael Guillen weighs in on planets. He is right, saying concepts like “planet” shouldn’t be voted on. The point of science is to evolve our conceptualization of things. There is a deep, interesting history of how “planet” evolved in the tug of war between science and culture.

There were four main events in the evolution of “planet.” The first was the Copernican Revolution, where scientists rejected the dynamical concept — wandering stars orbiting Earth — and replaced it with a geophysical concept: Planets are bodies like Earth, regardless of what they orbit.

That concept was embraced by astronomers for over 300 years until sometime in the 1900s. Around 1920, evidence shows that scientists simply forgot that moons are also a type of planet. That’s when the textbook definition of “planet” stopped including moons as planets.

I say they “simply forgot” because we can see there was nothing happening in planetary science that drove a change in the definition. Instead, we see use of terminology slowly drifted as a pure Gaussian — non-driven diffusive process — until moons were rarely called planets.

That’s when textbooks stopped giving the historic definition that existed for over 300 years since Galileo. The idea that planets have to directly orbit a star was introduced by default, no scientific reason. Dynamics had made a sneaky comeback into the concept of a planet.

That laid some of the groundwork for the bad vote that happened in 2006.

Culture bias affects everyone

When we ask, why did astronomers default to putting “orbits” back into the concept of a planet, there’s no known answer except it must’ve been cultural bias. Scientists are affected by culture, too.

And why does culture default to making moons not planets, holding a concept that planets must orbit a star directly? I can’t see any answer in the record other than it is similar to the older geocentric view, where planets are orderly in a tidy sequence.

On the other hand, in the 1960s, planetary scientists started calling moons “planets” again. By then, spacecraft missions were visiting those planets, and we rediscovered that the historic concept we had from Galileo — purely geophysical with no reference to what a body orbits — is still useful.

But sadly, the community was fractured by then, and at most, astronomers weren’t dealing with the geology in comparative planetary. So, they never went back to the historically useful concept of “planet.” Most astronomers kept orbital dynamics as part of their concept.

Historically, planets that orbit a star directly are called “primary planet” — or just “planet” for short — while “secondary planets” are also called “satellite” or “moon.” “Secondary planet” is too verbose, so it fell out of favor. Thus, astronomers forgot that moons are planets.

After the Copernican Revolution, that was the second change that happened in the concept of a planet. A generation of astronomers were not explicitly taught that dynamics is irrelevant to planethood. That was all it took to get screwed up.

It was 1920 to 1960 when that occurred.

Planetary trailblazer

To recap: Galileo found lunar mountains, so he forged a new concept of “planets.” They are geophysical objects like Earth — including moons. This new concept was born from alignment with new theory, and so it replaced the old dynamical concept. He had to fight culture over this.

Then, over a period of 300 years, astronomers kept including moons as actual planets, because there was no change in the theory and thus no motive to forge a new concept of “planet.” Every textbook for 300 years explicitly said that moons are planets.

But, slowly astronomers changed terminology and forgot the term “secondary planet.” There was no science driving that change. Nobody was arguing that moons are different than planets. On the contrary, the commonality of moons and primary planets was often used in scientific papers.

So the second major change in the “planet” concept appears to have been primarily a cultural influence rather than scientific. It will take more space to fully make this argument, and a paper is forthcoming.

The third major change in the concept of “planet” involves the size of planets. There was a long trend through the 1800s of finding ever-smaller asteroids, and they were all included as primary planets. They were abruptly made non-planets following a paper by Gerard Kuiper in 1953.

Pierre-Simon Laplace’s old planet formation theory was believed to be proven by the asteroids. So, a concept of “planet” that included asteroids was aligned with that theory. Kuiper’s 1953 paper on accretion theory split the “planet” concept into two groups, so asteroids became non-planets.

The bibliometrics shows that astronomers quickly stopped calling asteroids “planets” in the late 1950s. Papers on theory called them planets right up to Kuiper’s 1953 paper then immediately stopped calling them planets.

So, what was the essence of this third concept change?

Life enters the fray

Galileo gave us the concept that a planet is a geophysically complex body like Earth. All astronomers began arguing the complexity of all the planets, even the idea they all possess life. By including the ever-smaller asteroids, we were undermining that concept, in effect.

By removing asteroids from the concept of “planet,” scientists were restoring Galileo’s concept that they’re Earth-like complex geophysical bodies. This was motivated by science, aligning the planet concept with theory. This was good. That’s how science is supposed to work.

Strangely, in this third case, scientists didn’t have to fight culture, and they weren’t submitting to culture either. Culture had never accepted the asteroids as planets. Science happily moved to a concept that culture already held. Nobody got tried — like Galileo did.

The essence of this third concept change was that a planet is geophysically complex, but small asteroids are not. Papers argued that asteroid Ceres is a planet for precisely this reason.

This concept aligned usefully to support new theory, which is how science works.

Orbit-clearing invention

So now, the fourth major event in the concept of a planet: the vote in 2006. They said a planet is “an object that clears an orbit.” That is a completely different concept than we ever had before. It was designed to select roughly the same set of eight or nine objects, but to do so they invented an orbit-clearing idea, never part of the concept ever before.

It was motivated in the interplay of science and culture, again, but this time the astronomers unwittingly rejected science for culture. Look at the arguments on both sides.

As far as I can tell, the underlying motive was to preserve the idea that planets are “special,” reflecting an orderliness of nature that culture desires. It was easy to fall into that: The idea that moons aren’t planets already injected dynamics into the concept held by most astronomers.

It wasn’t motivated by newly developed theory like the case with asteroids. But presentism — wrongly interpreting past events by projecting current beliefs onto people who lived in the past — was used to misinterpret the history of how asteroids became non-planets.

Presentism is also what keeps astronomers nowadays from grasping that moons have always been true planets, since the Copernican Revolution and even before, and that until very recently “orbiting a star” was never part of the concept of a planet — except in culture.

This interplay of culture and science is fascinating. We see four different ways that it played out in the four different events affecting the concept of “planet.” It makes you wonder, why are planets so darned important to culture? Culture doesn’t care about the definition of beetles.