2020 will be a year to remember. Many people’s lives have changed trajectories in the last several months. Among my friends living in a metropolis before the pandemic, half is not there any longer, with the unclear prospect (and desire) of coming back.

Julia [this is a fictitious name] moved to London from a midsize town about a year ago. She was planning to buy an apartment and settle down with her family. Right before the pandemic, she came back to her hometown to sort out some issues and found herself stuck there in the blizzard of events that followed. She and her husband are now building their own house in the countryside. “The priorities have changed. The pandemic strengthened the feeling of precariousness of the big city life. I feel much more secure here, on my own land”.

Already before COVID-19 there was a growing trend to escape cities. It was fuelled by gentrification of “backwaters”; switch to flexible working and freelance, and — importantly — the high cost of life in big cities. The pandemic added its own tragic hue.

Science Behind: What was Wrong with the Urban Development?

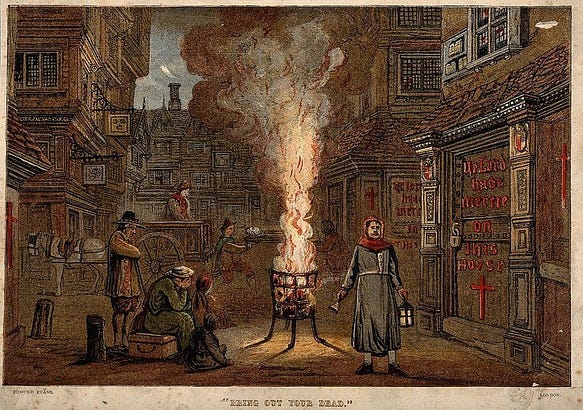

During the human history, many infectious diseases emerged in big cities. Plague, cholera and tuberculosis devastated cities and re-shaped them completely. This is not surprising. Big cities serve as transportation hubs and magnets for migration. Constant flows of people help further spread of diseases. Metropolises also have very high density of population who often live in sordid, unhealthy conditions. The COVID-19 was not an exception. The virus hit New-York, London, Paris, and other cities with millions of inhabitants.

The density of population becomes a problem when social conditions do not match up to the fast economic growth of mega-cities. We are not only talking about slums of San Paulo or Mumbai. In the pre-COVID world, healthcare and safety were often sacrificed to consumption “on steroids”. Tiny, cram-packed restaurants and bars in London. Companies squeezing people like sardines into open spaces to extract more productivity. Apocalyptic view of the New York subway at peak hours. Western cities showed the utmost recklessness in dealing with “black swan” threats to public safety. Bloated with blind confidence, we were so focused on eating, travelling, consuming that we let invisible ‘terrorists’ enter into the very heart of our social system — our big cities. The Coronavirus turned out to be the micro-biological analogue of 9/11.

The COVID-19 showed how precarious the current urban development approach was and how many things should change. Before the pandemic, urban economists argued that density was good. It allows cities to be significantly more productive leaving less environmental footprint. Now, the city planning departments are revamping their programs. They search to reduce the density to prevent uncontrollable spread of viruses. Yet, they are facing the serious dilemma: without concentration of people, resources, energies, big cities will lose the lion’s share of their appeal, both economic and socio-cultural. The solution could not hinge on reducing the density only. Examples of Seoul and Singapore, extremely concentrated cities that successfully contained COVID-19, suggest that it is not just density of population, but the city governance that matters most.

The pandemic has also revealed the staggering inequality of the big city life. The research found that denser cities witness increase in social disparities, as benefits of the city life are distributed very unequally. During lockdown this inequality became even more evident. Well-off people had opportunity to isolate in large apartments or summer houses, while poorer people were more exposed to the virus. The COVID-19 is sometimes called the disease of social periphery. “Social periphery” means the poor class that often gravitates to big cities in search of “better life”. These people are struck the most by threats like the Coronavirus. In the wake of the pandemic, cities will need to reduce this inequality in provision of basic services and exposure to risks. Otherwise, their prospects might become quite bleak.

Death of Big Cities — Rise of the Hinterlands?

So, will big cities slowly die after the 2020 shock?

Some negative trends have already been there. The research shows that cities in the wealthy countries reversed their growth, as urbanites started to move to smaller towns and countryside.

The pandemic is going to accelerate this trend. First, there is a shift to more flexible, remote working. Many companies have announced their plans to encourage working from home until Christmas. Others (like Facebook, Twitter and Coinbase) are moving part of their staff to the permanent remote working. Without the need to commute daily, people are considering transfer to suburban areas where life is cheaper and which are perceived as “safer”. There is even a more radical movement. According to one poll, nearly a third of Americans are now considering moving to rural areas. The pandemic brought sheer realisation of fragility of the life in big cities. When everything goes well it is comfortable and smooth. But once a calamity hits, urbanites have to rely on others for their essential survival needs. If there is no supply of food, water, electricity, the big city becomes a deadly trap. The Coronavirus pandemic might be just a mock-up of what can happen.

This fear of being cut off the basics is driving many people to live off-the-grid, in a completely self-reliant mode — with own electricity generator, water supply and the food grown in the kitchen garden. City dwellers take a fresh look at the simple village life. The self-isolation also revealed that we do not need to live in the midst of the anthill to stay connected. Slower life pace outside big cities releases more energy for creativity and interacting with your friends and family, in-person or virtually.

Julia said that moving out of a big city was liberating. “I gained the freedom to organise my life the way I wanted with the limited resources I had. I am a freelancer, so I can work from any place where there is Internet connection. I have more free time to spend on productive work, recreation, being with my family. It seems like the big city gives you a lot — money, opportunities, connections. But it also takes back a lot. In the end you are not a winner in this equation…”

This backlash against urbanisation will push big cities to revisit the ways to attract and retain talents after the Corona crisis.

Big Cities Get a Second Chance

In the wake of the pandemic not all big cities will die, but all will be changed.

Big cities are an essential part of our culture and social progress. It is where all big talents, thought leaders and rebels mix and mingle to create the melting pot of ideas. It is where the “future comes to audition”. While the job opportunities might be shifting to less dense areas with lower prices and higher quality of life, big cities will continue to thrive as long as they keep the status of cultural and intellectual centres attracting young people in the search of success.

The pandemic and the following economic shock might even have a revitalising effect on megapolises. The exorbitant life costs will go down; accommodation will become more affordable; public transport — more safe. This, in turn, will attract new labour force, invigorating the withering city life. Young people will keep on coming to big cities to study, network and lay the ground for their careers. The success of big cities will depend on how well they will match the increasing standards of the post-millennial Generation Z scarred by the bitter experience of the pandemic.

The urban development in the next ten years will move towards more sustainable and smart cities. First, cities will become more fragmented with neighborhoods becoming self-sufficient. For example, Melbourne plans to give residents ability to meet all their daily needs within a 20-minute walk from home. The mayor of Paris suggested turning it into a 15-minute city to reduce commuting and stress and “improve overall quality of life”. Second, pedestrianisation and micro-mobility schemes will gain popularity with less reliance on the centralised public transport. Third, we will see the decay of high-street retail and mammoth shopping malls. Urbanites will switch to virtual shopping — the habit formed during the pandemic. Businesses will have to rethink the use of office centers. Less and less companies will own large downtown headquarter buildings. High-quality public spaces, green zones, co-working and creativity areas will take place of shopping malls and office centers. Finally, city management will need to find a solution to inequality born out of cities’ growth and allocate the burden of the city life (e.g. housing expenses) more fairly.

In this scenario, big cities will again become places to breathe and live. We will witness the rejuvenation of megapolises. At the same time, the city life will likely become transient, as we already see in super-expensive hubs like London. People will stay there 5 to 10 years and move to smaller cities as their wealth and freedom of choice grows. This will make the big city economy more sharing than owning. Fewer people will buy their own apartments, knowing that they will eventually move out. Big cities will resemble the huge Airbnb, with the whole buildings and blocks owned by institutional investors and rented out to lodgers. People will be more ready to move out in case of urgency (like the bigger pandemic), supported by the trend to higher mobility and more flexible career paths.

I refuse to believe in the death of big cities. I hope we will not see the gloomy scenario where big cities become the last refuge of marginalized, poor, desperate and sick — giant lazarets where people go because there is no better place for them. However, the transformation is inevitable. In the next decade, big cities will compete for talents not with each other — but with midsize and small towns offering more safety, lower costs and a balanced lifestyle. The pandemic gave big cities a chance to get on track of these changes faster — it’s up to city management not to waste it.