We are on the verge of entering a new and better world.

A few days ago, I was driving around tending to minor errands that have been accumulating over the last week or so. It was late afternoon and since I skipped lunch, I was beginning to get hungry. I thought I’d swing into Subway and order one of their low-calorie cheese and broccoli soup offerings to hold me over until dinner. They’re a decent price, at least before the COVID-19 lockdown, and not bad nutritionally.

Even though there were no customers lined up at the glass counter watching their sandwiches being made, the two women behind the counter were working like mad, throwing together a half dozen sandwiches.

“You here to pick up a delivery?”, one of them called out before I could even make it to the counter.

“No,” I said. “I just wanted a bowl of soup.”

“Oh”, the other one said. Even behind her mask I could hear the relief that I wasn’t picking up a delivery that wasn’t ready, combined with the stress of an additional order.

“OK”, she said, quickly scooping up a handful of olives and spreading them on one of the foot-long sandwiches in front of her, then reaching for cheese and salami.

Apparently, they were overwhelmed by delivery orders that had been called in via old-fashioned phone orders and online apps. Customers have always called in orders and picked them up, of course, but the last few months have seen an explosion of online delivery platforms.

There is GrubHub, DoorDash and Uber Eats of course, but Instacart has joined the fray along with Goldbelly, and Fresh Direct. Established food and grocery brands like Dominos Pizza and Whole Foods also have their own proprietary apps. Just login, order what you want, pay with your smart phone and food is on the way.

“I’ll get done with these super-fast and get you your soup…Wait a minute. I’m not sure we even have any soup.” She didn’t even pause assembling the sandwiches on the counter in front of her.

Right on cue her co-worker turned form sliding sheets full of dough into the oven, and checked the soup cauldron.

“Just a little chicken noodle in the bottom. Looks pretty thick.” She turned back to her bread making, pulling empty dough sheets from a cupboard under the counter.

I wasn’t sure if thick chicken noodle soup at the bottom of the cauldron was a selling point, meant to discourage me from placing an order or an irrelevant detail in the chaos of overwork.

“Never mind”, I said. Obviously, a bowl of fresh broccoli cheddar was a little too much to expect. “I’ll call in my order ahead of time like everyone else.”

As I walked across the parking lot I wondered if my experience were a harbinger of a new phase of retail sales.

It occurred to me that instead of a walk in sale supplying a bit of profit to the company I had been an obstacle to sales, undermining profitability.

Imagine! Subway had been too busy with delivery orders to serve a walk-in customer!

The option to call in orders is undermining one of the fundamentals of the Subway business model – customers seeing all the delicious fresh food assembled into their order. Part of the experience of eating a Subway sandwich is watching it being made.

COVID-19 suddenly made that aspect of the business model irrelevant. Now customers are far more concerned with avoiding COVID-19 than watching their food being prepared. Consumer demand is shifting towards maintaining social distancing by minimizing public outings, instead of participating in the “Experience Economy” that emerged in the 1990’s.

Ride sharing platforms like Uber and Lyft are losing their shirts because people are suddenly staying home. In response, Uber is moving into the delivery business in a big way. Uber lost $1.8 billion dollars in the initial wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and bought Postmates, expanding Uber Eats to convenience stores, pharmacy and grocery delivery.

“The vision for us is to become an everyday service,” says Dara Khosrowshahi, CEO of Uber. “Postmates is a great step along that vision. Anyplace you want to go, anything you want delivered to your home, Uber is going to be there with you, and we think these everyday frequent interactions create a habit, create a connection with customers.”

He’s onto something, but maybe not for the reasons he thinks.

For years consumers and retailers have been slowly inching towards contactless payment – waving a smartphone or card over a sensor to pay for goods and services. Neither consumers or retailers had much incentive other than convenience to jump into contactless payment systems, but COVID-19 has changed that.

Fear of contracting the virus is driving a surge in contactless payment systems.

According to a Mastercard survey 80% of global consumers are now using contactless payment systems. In the United States 60% of people not yet using contactless payment systems plan to do so soon.

What we are seeing is the emergence of “Contact Free Customer Service”. And it is going to make retail as we have known it unrecognizable.

It’s already happening in restaurants. Order for Me allows restaurant patrons to view a menu and place orders, either individually or as a group. Payment is made contact free with a smart phone or card. No waitstaff required, and robots are waiting in the wings to deliver meals to tables; robot bartenders are already on the job.

Avoiding illness is only one factor driving the rapid adoption of Contact Free Customer Service. An even more powerful incentive is the move to a frictionless digitized consumer economy. Technology is making remote transactions of all kinds cheap, instant and convenient. That applies not just to financial transactions, but also to labor transactions and customer service.

The cost savings driving the adoption of remote work is moving to retail trade.

When large businesses saw how much money could be saved by moving workers off-site, the work from home movement suddenly changed the concept of employment. Work no longer means a daily commute from a computer at home to a computer at work. Because personal computers are ubiquitous work can be done from anywhere.

This change wasn’t due to a recent technological development. We’ve had the technology to work from home for years. Writers, programmers and graphic artists have been making a living remotely for decades. What changed was the way large organizations look at the way work is performed. The onset of COVID-19 thrust many formally hesitant businesses into allowing employees to work from home.

For workers who sit in front of computer screens all day, it is irrelevant whether they are sitting in their own home offices or in an office supplied by the employer. No matter the location, their work is done via computer terminal so it makes little difference where they do their work. Qualms about productivity and staying on task were quickly put to rest when employers began using affordable off the shelf surveillance software to keep tabs on their homebound employees.

It didn’t take too many days of dark and silent empty cubicles to make an impression. Business owners and managers soon learned that business went on as usual with employees working from home. The need to keep employees on site no longer justified the cost of the electricity, HVAC and office real estate needed to hold them – not to mention the real estate required to park their cars.

Global Workplace Analytics estimates that companies can save $11 million for every 1000 remote workers because of increased productivity, lower office space costs, lessened absenteeism and superior disaster preparedness.

The cost savings of a remote workforce is so great that large companies are making sudden and dramatic moves. Recently Recreational Equipment Inc., (REI), abandoned its newly completed and very expensive corporate headquarters before ever moving into it in favor of a home-based remote workforce

Employers learned how much can be saved by separating workers from traditional workplaces.

Now retailers are taking the hint and realizing that vast amounts of money can be saved by keeping customers at arm’s length. Like remote workers, remote customers will save retailers boatloads of money no longer needed to accommodate their physical presence.

This trend towards distancing customers is nothing new. There has been a slow movement in using the internet to remove customers from retail spaces for years.

ATMs and online banking have been around for decades, and so many customers use the service that banks have been closing brick and mortar branches. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic branch customer traffic has fallen by a third.

Education has also been offloading students from physical campuses to online education. In 2017 about a third of undergraduates were taking at least one course online; almost 15% were enrolled in full time online programs. That number is expected to increase dramatically as schools rush into offering predominantly online programs.

Job hunting and employee recruitment have made the move to an entirely online process without fanfare. Almost all large corporations use Applicant Tracking Software, (ATS), to automate recruitment, hiring, onboarding and training. Online platforms like Career Builder and Indeed make applying for jobs a standardized mechanical process for job seekers.

Substantial savings are being realized just by physically distancing customers, clients and students and replacing face to face relationships with online interactions.

Now retail is catching up.

Online shopping has been around since Amazon started selling books back in 1994, and now is one of the biggest companies in the world. But Walmart and Target have moved online as well. Walmart is even launching an Amazon Prime competitor called Walmart+. There is no longer any need to physically go to those stores even to pick up something you’ve bought. The advent of delivery services has eliminated the need even for that contact.

This is one of the reasons malls have outlived their profitability. The stores and promenades were luxuriously spacious, but every square foot was expensive, and acres of parking lots required maintenance and lease payments even when empty. The asphalt was just as costly as nearby retail or office space.

Eventually the exorbitant cost of commercial real estate out stripped the premium mall-based retailers could charge customers. The experience of shopping in an opulent mall was no longer worth the inflated prices mall-based retailers were charging. As more people made less money, mall shopping became unaffordable and online sales took off.

Without customers roaming about, the need for expenses like parking, cashiers, stockers and in store marketing disappears. There is no need for displays, signage or fronting shelves. That means fewer employees, and fewer employees always means lower costs, more efficiency and an improved bottom line. That’s why investors flock to companies announcing layoffs or the adoption of technologies that eliminate positions held by humans.

The model for the future of retail are Amazon Fulfillment Centers.

These automated warehouses exclude customers in favor of efficiency and cost savings. Robots now assemble orders from racks stocked by other robots, and humans are needed only for final packaging.

But this might not be the end of malls.

According to USA Today Amazon is expressing interest in converting abandoned anchor stores in empty malls into fulfillment centers. The sticking point, is, of course, expense. Amazon is usually drawn to real-estate on the fringes of metropolitan areas because it costs less. But malls have largely outlived their utility and there is not much competition for converting them into something profitable.

Retail business models requiring huge amounts of real estate were a hit in back in the 20th century, but they are obsolete in the modern digital economy. The twin challenges of the cost of real estate and diminishing personal wealth have put an end to that business model. There is a certain irony that malls — relics of mass employment, mass marketing and a consumer economy — are being considered for conversion to robot dominated distribution points in an expanding digitally driven economy.

The final mile of the consumer value chain, where customers take possession of their orders, is also becoming part of Contact Free Customer Service.

The common sight of UPS, Fed Ex, and Prime delivery trucks racing about is an artifact of a bygone time, like milkmen and mailmen delivering door to door. After all, vehicles powered by internal combustion engines requiring a massive network of asphalt are 19th century technologies that grew to maturity in the 20th century. Using such an archaic system for delivery is inconsistent with a 21st century retail landscape in which every other aspect of retail is cheap and immediate.

Exactly what the final mile of delivery will look like in the near future is unclear, but Amazon is already expanding its fleet of autonomous delivery vehicles to new cities. These vehicles are little more than carts rolling along suburban sidewalks, but they mark the introduction of contact free delivery. The days of harried delivery drivers trotting from house to house, leaving packages in front of doors or tossing them over backyard fences won’t last forever.

Aerial delivery via drones is under frantic development, but technical challenges and regulatory hurdles make this a delivery system for the future. It may be that aerial delivery is better suited to replacing long haul trucking than final mile delivery. New technologies like rigid airships powered by powerful jet or turbine engines might be the death knell for the trucking industry.

We’ve been through these upheavals before and we will get through this one, too.

COVID-19 has accelerated the changes brought on by the end of the industrial economy. Economic transitions like this are rare, but always very difficult for the people living through them. When the industrial economy began challenging and then replacing the agrarian economies of Western Europe and North American in the 18th and 19th centuries our ancestors faced the same hardships and challenges we are facing today.

Times were hard.

But times got better, too. The industrial revolution lifted the western world out of abject poverty and blighted existence that had lasted for tens of thousands of years and created the greatest prosperity for the largest number of people the world has ever seen. Now it is extending into the remotest parts of Africa and South America.

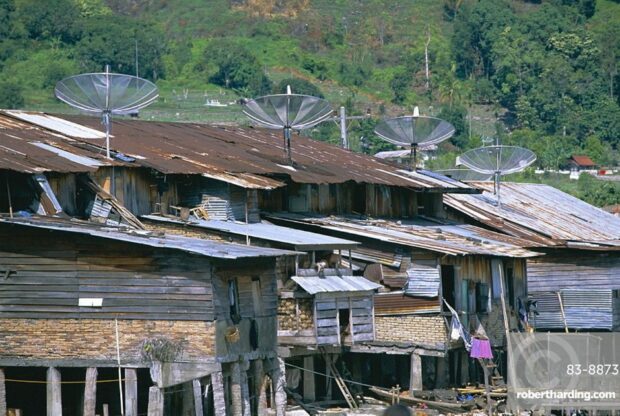

Another optimistic aspect of our present transition is that progress is happening increasingly faster. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries African nations skipped right past networks of expensive telephone wires and poles and quickly adopted wireless technology. It’s commonplace to see solar panels and satellite antennas in front of traditional huts.

Our adoption of emerging technologies will come more quickly than most people expect, but the economic recovery from COVID-19 will take longer. Widespread distribution of a vaccine and the achievement of herd immunity will take years, not months.

But that hardship will not be without its advantages. It will push us faster and further than ever away from the industrial economy of the 19th century into a wondrous world that will prepare humanity for the 22nd century.

If you liked this article I’m sure you’ll like this one from DDI, too: What Happens next?

You may enjoy these Medium.com articles also:

The Startling Truth About the Looming COVID Recession

The COVID Cashless Economy is Delivering the End of Retail Right to Your Door

The Incredible Opportunities Coming with the Post COVID-19 Economy

Start Learning About Economics with These Painless, Inexpensive and Interesting Books

Coronavirus, Media Sensationalism and an Astonishing High-Tech Future

Read more at VicNapier.com and my Medium.com page.

Links may lead to sites where the author has an affiliate relationship