Step aside science nerds, an economist needs to say something…

To some, colonizing Mars is an exciting future to look forward to. It would be an exemplification of the human spirit and a mark of our achievements as a species.

To others, the colonization of Mars is a pointless endeavor. It seems to offer little return on substantial costs, especially in the short term. Why not fix the problems here on Earth first? Can we justify such an onerous project while nearly one billion of our current planet’s inhabitants don’t even have enough to eat? Or while cancer and other diseases continue to take our loved ones away from us before their time?

While I agree that we should focus earnestly on Earth’s problems, it is also apparent that looking beyond home is necessary for the progress of mankind and for its very survival. Stephen Hawking believed that we need to colonize another planet within 100 years to escape climate change, asteroid strikes, resource depletion, and apocalyptic wars to name but a few potential catastrophes.

“If the human race is to continue for another million years, we will have to boldly go where no one has gone before,” — Stephen Hawking, 2008

Scientists and engineers generally have the loudest voices regarding this subject. But that shouldn’t mean barring economists like myself from the conversation. After all, we will need to play our part in making sure the Mars colony becomes economically self-sufficient, if not prosperous. We need to design a policy to leverage the benefits of colonizing Mars while minimizing the costs. It also provides an unprecedented opportunity to create and study growing an economy from a blank slate.

Growing an economy from nothing

Economists have a unique challenge in Mars because most growth challenges have some foundations to push off from. Growing a Martian economy would thus require radically different approaches. There are many competing ideas on how to do it and there is no clear answer.

A potential major source of revenue for the extraterrestrial colony is real estate. A wave of colonists will certainly create a real estate market that could boost the Martian economy considerably. With sufficient property rights, it could be a crucial source of income for the colony. This need not involve setting up a legal system on Mars; the property registry of say, the USA would be adequate. Estimates suggest that land values on Mars could grow over 100-fold (to $36 trillion) once terraformed. So once enforceable property rights are in place, private owners should have the incentive to terraform their land themselves, as long as the cost of doing so is limited by technological advancement.

“Their motives for [immigrating to Mars] will parallel in many ways the historical motives for Europeans and others to come to America, including higher pay rates in a labor-short economy, escape from tradition and oppression, as well as the freedom to exercise their drive to create in an untamed and undefined world. Under conditions of such large scale immigration, sale of real-estate will add a significant source of income to the planet’s economy.”-Robert Zubrin

I am more apprehensive about the significance of a Martian real estate economy. Zubrin, a famous author and aerospace engineer, overestimates people’s zeal-depending on droves of ordinary people sell all their terrestrial possessions to buy land on (on top of a ticket to) Mars may be naive. By his own estimates, Zubrin thinks a habitable dome measuring 100 metres in diameter can enclose $1,000,000 of real estate value. Though I claim no expertise in engineering matters, it seems highly improbable that this will cover the value of construction of these domes; decades of technological progress will be needed to reduce construction costs before this happens.

Raising the cost of Martian real estate to cover these expenses would be so substantial as so as to deter the immigration of colonists. Then land would certainly be bought exclusively by people who are wealthy enough to do it simply for the novelty of it. Then there question of who has the right to sell the land on Mars. Would it be SpaceX or the US government? Many such complications will arise under a system of private land ownership, which leads me to suggest that some sort of public land ownership among the colonists will be required- at least in the short term.

A better possible economic backbone for the Martian economy could be natural resources. Precious metals from the Red Planet such as gold, platinum and europium could be exported back to Earth for a very high profit as long as transportation costs are kept in check. This would perhaps be done by using reusable rockets to deliver the cargoes into Mars orbit, and then continuing the journey to Earth using cheap and expendable chemical stages (which could even be manufactured on Mars).

Planetary scientist Gary Stewart claims we can cut costs further by establishing an automated mining facility in a metal-rich crater on Mars. Robots could survey, extract and refine the metals themselves. The metals could then be fashioned into bullion, electronic components or jewelry with the aid of techniques like 3D printing. Stewart claims the facility would be self-sufficient with solar panel farms, local ice and salt deposits. He also contends that the facility could offer lucrative returns over time, allowing subsequent mining facilities to be established. Therefore, it is perhaps possible to lay the groundwork for a Martian export economy before we even set foot upon the planet.

Of course, we need to walk before we can run. Before we can think about the Red Planet, it is sensible to practice running a natural resource-centric economy using the Moon. Large profits could be made through the Moon’s supplies of Helium-3: the isotope could be exported back to Earth for use in thermonuclear fusion reactors. We should also acknowledge that it’s hard to gauge whether there are large bodies of precious metals on Mars in the first place.

More verifiable are the riches of the asteroid belt. These could be extracted if we use Mars as a base. Though asteroid mining poses noteworthy financial and technological challenges, Goldman Sachs believes this possibility is within reach. Profits should comfortably offset any costs and transform the economies of both Mars and Earth. Goldman even predicts that asteroid mining will produce the world’s first trillionaire, though it should be acknowledged that this individual will likely be a billionaire to begin with.

Some are skeptical about the cost-feasibility of a material-export economy altogether, such as SpaceX’s Elon Musk and previously mentioned Robert Zubrin (though Zubrin sees some potential in extracting deuterium, which is used as a moderator in nuclear fission reactions). Instead, both believe that the greatest economic potential is in licensing intellectual property and selling research back to Earth. A range of academics, from scientists to historians, can see how there could be a deluge of inventions from travelling and living on Mars. The planet’s challenging conditions could spur the development of new technologies just as labour scarcity in 19th century America led to a flood of inventions.

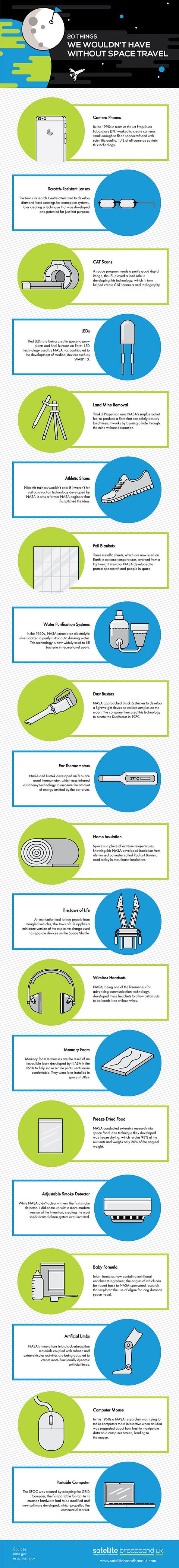

It is very difficult to foresee how technology developed for the Mars project could impact everyday life, but there is undoubtedly a large scope for innovation from space exploration. Many inventions that originated in the space sector have made their way to the consumer space: camera phones, baby formula, memory foam, invisible braces, computer mice, water filtration systems, prosthetic limbs, LEDs, freeze dried food- I could go on. The idea is that innovation from Mars colonization has huge potential to transform economies.

Building this economy on Mars will not just benefit Martians and their descendants- those who remain on Earth will also enjoy economic gains.

As briefly discussed earlier, the process of colonizing Mars will act as a ‘pressure cooker’ for innovation, which Earth can benefit from. Similar to the “New World”, Mars will be a society of self-selected immigrants, operating in a harsh, labor-short environment in which skilled workers will earn wage premiums. Patenting inventions created under conditions of necessity on Mars will produce the wealth needed to support the planet’s development. These innovations will raise terrestrial living standards and destabilize tendencies that would otherwise lead Earth towards technological stagnation.

Moreover, one can highlight the geopolitical benefits of a permanent settlement on Mars. The United States and China are the most likely colonists, and the winner of this new space race could determine the leading economic and political power for the remainder of the 21st century.

In addition, Neil deGrasse Tyson has suggested how Mars could “galvanize an entire generation of students in the educational pipeline to want to become scientists, engineers, technologists, and mathematicians”, just as the Apollo missions did. This intake of people into STEM professions could make for a more dynamic and highly-skilled economy.

A Need for Hesitation

Though I have discussed the economics of colonizing Mars, we must acknowledge that it will be a while before we should even start to do so. Namely, the cost of transport needs to be drastically reduced for both people and goods first. Currently, the cost of sending one person to Mars would be $10 billion. Elon Musk is leading a relentless technological drive to push this figure below $200,000 per person. He needs to get close before we start sending the first colonists there. We also need better technologies to build the colony and protect ourselves from Mars’ radiation.

Furthermore, we need to be overwhelmingly confident that there isn’t some form of Martian life that we could endanger with microbes from Earth. Indigenous microbial life on the Red planet would be a monumental biological discovery, especially if they had a wholly unique biochemistry.

The future is exciting. Scientists, economists, and everyone in between should start thinking about and be looking forward to it. But it’s not here yet.