Over 28 years, four international financial crises occurred: the Latin American, the Japanese, the East Asian, and the Global Financial Crisis. With a crisis occurring every seven years on average, the international financial system grew historically fragile. These four crises reveal the dangers of global capital flows in a floating exchange rate system. In every crisis, capital imports poured into a country experiencing financial innovation, increasing asset values and credit availability. Meanwhile, appreciating currencies improved investors’ returns, and their risk preferences increased. As investors’ financial and economic outlook grew unrealistically optimistic, increased leverage generated instability in the domestic financial and banking system. Ultimately, a minor shock cascaded the fragile financial system into crisis: international investors sold assets and reduced lending, causing a crash in asset values. Falling currency values exacerbated and deepened the crash as dollar-denominated debts became more expensive at the worst moment. While the once-booming market suffered, a new system of global capital flows would emerge out of the crash, eventually laying the foundations for the next bubble and international financial crisis. Floating exchange rates have augmented the rise of bubbles, exacerbated the crash of crises, and increased the likelihood of new bubbles.

Each bubble originated from some financial innovation that caused investment to appear less risky, which caused credit to expand in the burgeoning country. In the 1970s, before the Latin American crisis, the popularization of offshore banking increased credit availability to Mexico and other Latin American countries. In the mid-1980s, the Japanese government introduced legislation that liberalized their financial markets, causing a surge of capital inflows. In the early 1990s, the creation of Brady bonds and emerging markets as a new asset class reduced the risk of investing in East Asian countries such as Thailand and South Korea. At the beginning of the 2000s, the securitization of mortgages significantly reduced the risk of purchasing mortgages for lenders. While the four crises have significant differences, a pattern emerges from their rises to their crashes. At these early stages, no bubbles formed yet. New financial innovations warranted greater capital inflows.

The heightened investments improved the economic performance of the innovating countries. GDP and income grew rapidly. Manufacturing productivity and employment benefited from the increased investment. The host country’s economy became very strong. However, this stage of stable economic growth and robust finance was transitory. As financial and economic outlooks improved, lenders and equity investors took more risk. Greater asset values, expanding credit, and appreciating currencies complemented each other as they introduced more risk into the robust financial system.

Positive economic performance led banks to increase their lending. Capital inflows increased, causing the country’s currency to strengthen. Meanwhile, investors purchased more stocks as their returns increased from higher asset values and appreciating currencies.

Economic robustness caused international lenders to expand their loan books in search of higher returns, leading to higher external indebtedness for the rising countries. In the decade leading to the Latin American crisis, external indebtedness in Mexico increased by 20 percent annually. Credit expansion fueled rising asset values, including in stocks and real estate. Higher asset values warranted further credit expansion, forming a positive feedback loop. The expanding credit system was fueled by perpetually growing confidence in the improving economic and financial outlooks.

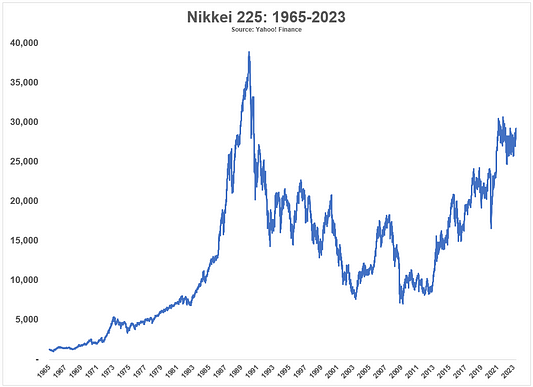

Furthermore, once lenders ran out of responsible borrowers, they sought increasingly risky debtors. In the US, subprime mortgages grew from 5 to 20 percent of national mortgages. Riskier debtors paid higher rates, and the financial and economic outlooks justified increased risk-taking. Japanese lenders began offering 100-year, three-generation mortgages. By the end of the boom, Japanese homeowners started taking out loans to pay their mortgage payments, meaning both lenders and homeowners expected the increase in the debtor’s property value to exceed the interest payment. Lenders and investors made increasingly risky decisions as financial and economic outlooks improved, causing the credit system to swell.

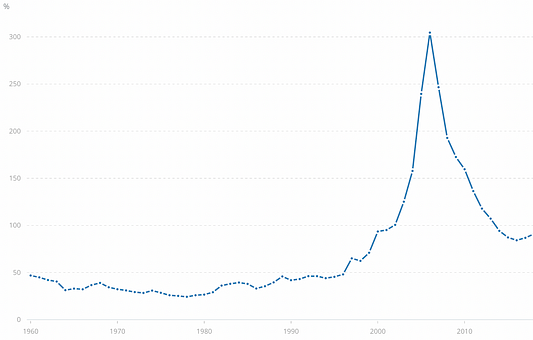

All financial bubbles (and crises) are caused by overleverage; however, the unique aspect of the four recent international bubbles has been the compounding accelerating forces of floating exchange rates. The Japanese Yen appreciated by 50 percent from 1985 to 1987. During the Icelandic housing boom in the early 2000s, the Krona strengthened by more than 30 percent. Appreciating currencies improved investors’ expected returns, leading to further capital inflows–raising currency prices even further. Thus, currency appreciation produced a positive feedback loop that increased asset values, compounding investors’ improving outlook.

The combination of the external credit and currency feedback loops caused asset markets to surge. In the first half of the 1990s, the stock markets in Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia increased by 300–500 percent. Real estate markets rose as lenders seeked increasingly risky mortgages. The Japanese real estate market grew to twice the value of the US market, even though Japan is five percent of the area of the US. As market participants’ outlooks improved, higher risk-taking led to absurd returns.

Increased risk transformed the financial system into an overleveraged, fragile structure. Financial institutions held inflated external liabilities with little capital. Before its insolvency from mortgage defaults, Lehman Brothers possessed a debt-equity ratio of 60. Financial institutions like Lehman can not survive minor market turmoil with such small capital margins.

Once all four international bubbles developed into fragile financial systems, the bubbles popped from minor shocks that a robust system would have survived. In 1979, the Federal Reserve’s contractionary monetary policy caused a crash in Latin American asset values and a rise in defaults. By 1991, the Japanese central bank authority halted the growth of real estate prices in the interest of the system’s stability; however, the fall in prices led to a doom loop of mortgage defaults that caused a financial meltdown. The East Asian Financial Crisis originated from the assassination of a Mexican presidential candidate in 1994, causing lenders to reduce their exposure to all emerging markets. Then, in 1996, significant loan losses for Thai consumer banks accelerated the crisis into a meltdown. The Global Financial Crisis started from a housing meltdown in the US that was caused by subprime mortgage delinquencies. The US crisis spread to the rest of the world, creating the largest financial crisis in history. Interestingly, another bubble did not emerge after the GFC; however, the extent of the global financial meltdown and recession may have meant hot money could not seek refuge in a new country after the GFC.

While all these crises consisted of an overextension of credit, currency depreciations exacerbated every crisis. As international investors reduced their exposure to a country in crisis, the host country’s currency fell. As the currency depreciated, the cost of dollar-denominated debt increased–debt servicing became more expensive at the worst moment. Furthermore, whenever a currency crisis occurred, a banking crisis was sure to follow. The increased cost of debt from a currency crisis leads to domestic defaults that cascade into a financial meltdown.

Furthermore, the fall in one currency can trigger a contagion effect that causes a financial crisis in one country to spread to other economies in fragile bubbles. For instance, the decrease in the Thai Baht at the start of the Asian Financial Crisis led to currency depreciations greater than 30 percent for all currencies on the Asian arc, excluding the Chinese yuan and the Hong Kong dollar. The increased external debt servicing and contagion effects of currency depreciations make international financial crises more severe than endogenous domestic meltdowns.

As international investors fled from one international financial crisis, they provided the capital inflows that fueled the next bubble. For instance, a surge in US investment inflows coincided with the fall in East Asian currencies at the end of the 1990s. These inflows caused the 2001 US stock bubble and led to a massive jump in housing starts in 2002. Thus, bubbles do not just originate from financial innovations; the new inflow of volatile global capital provides growth for up-and-coming, innovative countries. Due to hot money, the capital inflows for innovation are larger than what new financial innovation demands rationally or technologically. This critical connection is fundamental to the contemporary floating exchange rate system: in today’s international monetary system, floating rates do not just exacerbate financial crises, they also provide the impetus for the next bubble.

In a world of floating exchange rates, financial crises are prone to causing future crises. As hot money evades one meltdown to invest in the next big thing, new bubbles are formed by the volatile overindulgence in the following innovative country’s assets. The excessive demand of international investors expands the credit system of the host country. Financial and economic outlooks are improved, causing asset values, currencies, and credit to increase. Unique to floating exchange rate systems, strengthened currencies compound the manic effects of a usual bubble. As the bubble grows and institutions increase their leverage, the financial system becomes fragile. Ultimately, a minor shock overthrows the destabilized system. As investors flee from the carnage, the host country’s currency falls, exacerbating the financial meltdown. International investors then take refuge in the next big thing and do it all over again.